Why scale the Scaled Dot-Product Attention?

Mathematics and Logic Behind the Scale

Overview

The groundbreaking paper “Attention Is All You Need”1 (2017) introduced the Transformer architecture, marking a major breakthrough in the field of language modeling.

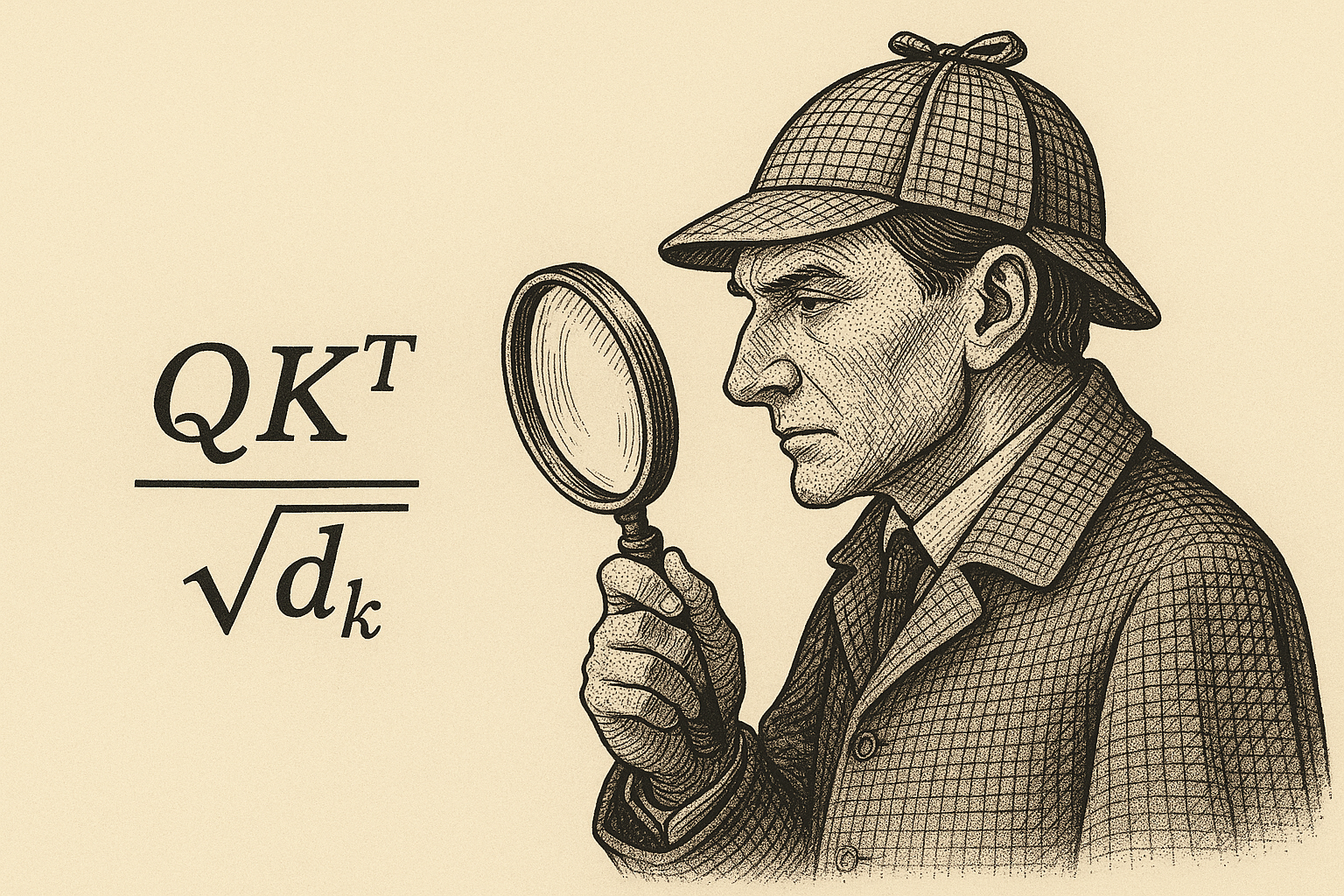

Among the many innovations in that paper, the Scaled Dot-Product Attention mechanism stood out as a core component of the Transformer. Here’s what it looks like mathematically:

\[\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^\top}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V\]The term “scaled” in this equation isn’t just a fancy name—it comes with solid mathematical reasoning. Unlike many hyperparameters in deep learning that are often tuned through trial and error or heuristics, the scaling factor $\sqrt{d_k}$ has a theoretical motivation.

Logic

The paper states:

“We suspect that for large values of $d_k$, the dot products grow large in magnitude, pushing the softmax function into regions where it has extremely small gradients. To counteract this effect, we scale dot products by $\sqrt{d_k}$”

Let’s dive deeper into this.

During initialization, weights are typically assigned randomly from a distribution with zero mean and unit variance. So, when we generate the query vector $( q )$ and key vector $( k )$, the dot product $( q \cdot k )$ will have a variance proportional to $( d_k )$, where $( d_k )$ is the embedding dimension.

Because,

\[\text{Var}(q \cdot k) = \text{Var}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{d_k} q_i k_i\right)\]Each $q_i$ and $k_i$ are independent, with $( \mathbb{E}[q_i] = \mathbb{E}[k_i] = 0 )$ and $( \text{Var}(q_i) = \text{Var}(k_i) = 1 )$. So each pair $(q_i \cdot k_i)$ is also independent.

Therefore:

\[\text{Var}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{d_k} q_i k_i\right) = \sum_{i=1}^{d_k} \text{Var}(q_i k_i)\]And for each term:

\[\text{Var}(q_i k_i) = \mathbb{E}[(q_i k_i)^2] - \left(\mathbb{E}[q_i k_i]\right)^2 = \mathbb{E}[q_i^2] \cdot \mathbb{E}[k_i^2] = 1 \cdot 1 = 1\]Hence, the total variance becomes:

\[\text{Var}(q \cdot k) = \sum_{i=1}^{d_k} 1 = d_k\]This shows that the variance grows linearly with $( d_k )$, while the mean remains 0.

As $d_k$ increases, the variance of the dot product grows—roughly scaling as $\sim d_k$. A higher variance causes the output of the softmax to become very skewed. In other words, the softmax outputs are extremely close to 1 for one position and near 0 for others. This can be understood with a simple example:

Suppose we have the vector: \(y=[0.2,\ 0.4,\ 0.1,\ 0.8]\)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

import numpy as np

def softmax(vec):

exp_arr=np.exp(vec)

return exp_arr/np.sum(exp_arr)

y = np.array([0.2, 0.4, 0.1, 0.8])

s = softmax(y)

print(f"Softmax of y: {np.round(s, 3)}")

Output:

1

Softmax of y: [0.202 0.247 0.183 0.368]

This produced a moderately spread probabilities. But now, consider multiplying the vector by 8: \(y\_scaled=[1.6,\ 3.2,\ 0.8,\ 6.4]\)

Since variance scales with the square of the scaling factor, the new vector has $( 8^2 = 64 )$ times the original variance. Now, applying softmax to this scaled vector would result in something like:

1

2

3

4

y_scaled = y * 8

s_scaled = softmax(y_scaled)

print("Softmax of y_scaled:", np.round(s_scaled, 3))

Output:

1

Softmax of y_scaled: [0.008 0.039 0.004 0.95]

Clearly, the output becomes extremely peaked, with one value dominating. But why does this “peaking” matter so much? To understand the issue, we must look at how softmax behaves during backpropagation, where we compute its derivatives.

Now, when we compute gradients during backpropagation, we rely on the derivative of the softmax function with respect to its input vector (pre-softmax scores). This derivative is captured by a Jacobian matrix:

\[J = \begin{bmatrix} s_1 (1 - s_1) & -s_1 s_2 & -s_1 s_3 & -s_1 s_4 \\ -s_2 s_1 & s_2 (1 - s_2) & -s_2 s_3 & -s_2 s_4 \\ -s_3 s_1 & -s_3 s_2 & s_3 (1 - s_3) & -s_3 s_4 \\ -s_4 s_1 & -s_4 s_2 & -s_4 s_3 & s_4 (1 - s_4) \end{bmatrix}\]- For $i = j$: $\text{softmax}’ = s_i(1 - s_i)$

- For $i \ne j$: $\text{softmax}’ = -s_i s_j$

Now, this Jacobian matrix can also be written more compactly using a small manipulation, as the difference between a diagonal matrix of softmax values and the outer product of the softmax vector with itself:

\[J = \begin{bmatrix} s_1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & s_2 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & s_3 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & s_4 \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} s_1 s_1 & s_1 s_2 & s_1 s_3 & s_1 s_4 \\ s_2 s_1 & s_2 s_2 & s_2 s_3 & s_2 s_4 \\ s_3 s_1 & s_3 s_2 & s_3 s_3 & s_3 s_4 \\ s_4 s_1 & s_4 s_2 & s_4 s_3 & s_4 s_4 \end{bmatrix}\]This entire operation can be compactly written as - $\text{softmax}’ = \text{diag}(\vec{s}) - \vec{s} \vec{s}^T$

In highly skewed distributions, most $s_i$ values are close to 0, so their derivatives become very small. This can be seen for our toy example.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

def softmax_derivative(vec):

return np.diag(vec) - vec.reshape(-1, 1) @ vec.reshape(1, -1)

J = softmax_derivative(s)

J_scaled = softmax_derivative(s_scaled)

print("Jacobian of softmax(y):")

print(J)

print("\nJacobian of softmax(y * 8):")

print(J_scaled)

Output:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Jacobian of softmax(y):

[[ 0.16125, -0.04988, -0.03695, -0.07441],

[-0.04988, 0.1859 , -0.04513, -0.09089],

[-0.03695, -0.04513, 0.14942, -0.06733],

[-0.07441, -0.09089, -0.06733, 0.23264]]

Jacobian of softmax(y * 8):

[[ 0.00776, -0.0003 , -0.00003, -0.00743],

[-0.0003 , 0.03722, -0.00014, -0.03678],

[-0.00003, -0.00014, 0.0035 , -0.00334],

[-0.00743, -0.03678, -0.00334, 0.04755]]

This leads to vanishing gradients, meaning the model’s parameters update very little (or not at all). As a result, learning slows down dramatically or fails altogether.

Now, the scaling factor $( 1/\sqrt{d_k} )$ is introduced to counter this effect. When we divide the dot product $( q \cdot k )$ by $( \sqrt{d_k} )$, the variance becomes:

\[\text{Var}\left(\frac{q \cdot k}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right) = \frac{1}{d_k} \cdot \text{Var}(q \cdot k) = \frac{d_k}{d_k} = 1\]This normalization keeps the variance of the scaled dot product around 1, regardless of the input dimension $( d_k )$. As a result, the softmax stays in a stable, responsive region, and the gradient flow is preserved.